The following story first appeared in the Indianapolis Star Memorial Day Weekend 2013.

Harry Arminius Miller, born in 1875, was a genius, artist, and perfectionist. What he did better than anybody of his era was build racecars. From the early ‘20s to the late ‘30s, cars and engines bearing his name dominated the Indianapolis 500.

“Miller was a genius, but not really an engineer,” said Donald Davidson, Indianapolis Motor Speedway Historian. “Miller would have a concept and Leo Goossen, his draftsman, would do the drawings. From 1923, Duesenberg was Miller’s only rival. They were practically unbeatable.”

Dedicated to Racing

Miller delved into racing by first improving carburetors, then pistons and fuel pumps. When race driver Bob Burman, who won the 1909 Prest-O-Lite Trophy Race in Indianapolis, blew his Peugeot engine in 1914, Miller rebuilt it. The following year, Miller built the aerodynamic “Golden Submarine” for Barney Oldfield. In 1919, Miller was paid $27,000 to build a car for Cliff Durant, son of GM founder Billy Durant. It was one of the last cars built before Goossen kicked the firm’s racing prowess into gear.

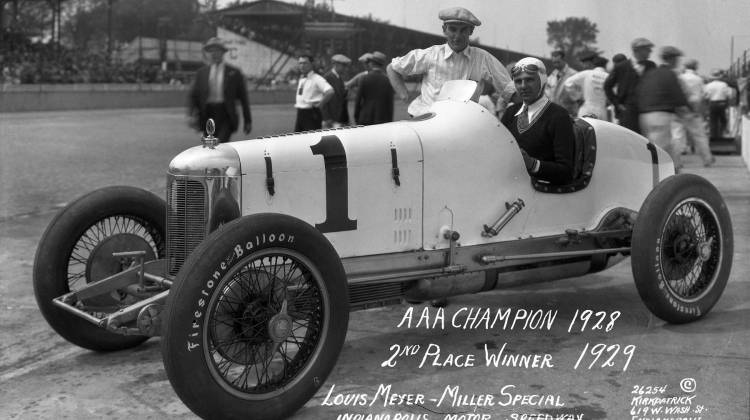

Prior to Miller, race cars were modified road cars. By contrast, Miller’s team built cars dedicated to racing. Success in The 500 first occurred in 1922 when Jimmy Murphy drove a Miller-powered Duesenberg to victory. Other notable winners include Tommy Milton in 1923, Louis Meyer in 1928/1933, and Ray Keech in 1929. In total, Miller engines or complete cars won the Indianapolis 500 twelve times by 1938 and gave rise to the influence of Fred Offenhauser, a former Miller engineer.

Advanced Technology

Although Miller built rear-drive and rear-engine racers, his firm is most famous for its supercharged front-drive cars. Contrary to modern rear-drive, mid-engine racers, front-drive had the same advantages in racing as it does in today’s road cars.

“Back then, tracks were oily and slick, which caused cars to spin,” said Davidson. “Front-drive cars pulled instead of fish-tailing. Having no drive shaft allowed a lower center of gravity for better handling. Front-drive was not a new idea, but was new to the Indy 500 when Jimmy Murphy drove one in 1928.”

After Duesenberg raced four supercharged cars in 1924, Miller developed his own supercharged engine. It did not win in 1925, but took six of the first nine places. Today, superchargers make cars like the Corvette ZR-1 powerhouses. Miller also experimented with all-wheel-drive and rear-engines before leaving racing forever.

Enduring Legacy

Beyond Miller’s record of success, it’s his attention to detail that amazes. His race cars display style and precision that befit a Bugatti. Grilles were often chrome and engine compartments were neatly tailored. It was artful over-kill for racing machines. But, what elegance.

“Miller did well in the ‘20s, but with the depression, his company was taken over by Fred Offenhauser,” said Davidson. “They were just beautiful cars; the ‘20s were the golden era of the American racing car. Miller was a perfectionist. He was an artist, not a businessman. Unlike Duesenberg, which sold road cars, Miller's reward was to sell more race cars.”

Miller died in 1943, leaving a legacy that endures.

Special thanks to Donald Davidson and Mary Ellen Loscar for their help with this story.

Storm Forward!

DONATE

DONATE

View More Programs

View More Programs

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.