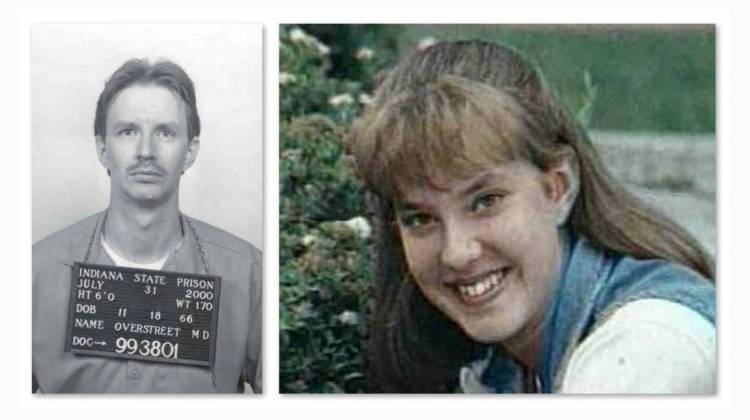

Michael Overstreet left, is on Indiana’s death row after he was convicted of killing Kelly Eckart, an 18-year-old Franklin College student.

TheStatehousFile.comINDIANAPOLIS – With the possibility of an execution occurring yet this year, Indiana officials are standing by their death penalty process, despite controversies over prolonged lethal injections in other states.

Doug Garrison, chief communications officer for the Indiana Department of Corrections, said officials are confident they have the right death penalty protocols in place to prevent the types of problems that recently marred executions in Arizona, Oklahoma and Ohio.

Michael Overstreet – who was sentenced to death in July 2000 for the 1997 murder, rape, and confinement of Kelly Eckart, an 18-year-old freshman at Franklin College – is likely to be the next inmate to face lethal injection.

“He is the closest to reaching the end of the appeals process,” Garrison said. No execution date is set, but Garrison said it could be later this year.

The last Indiana execution was that of Matthew “Eric” Wrinkles in 2009.

Overstreet’s execution comes as states across the nation are struggling to deal with criticisms over the punishment and problems securing the drugs necessary to do lethal injections.

Indiana and many states use a three-drug protocol to perform an execution, while others use two drugs and some just one.

The first drug in a two- or three-drug method has often been sodium thiopental, a sedative used to make inmates unconscious before other drugs are administered.

But the drug’s American manufacturer has stopped making it and its European counterpart has banned its export to the United States for executions.

Three states – Ohio, Oklahoma and Arizona – used the sedative midazolam in recent executions – and all took longer than expected, raising questions about whether the punishments crossed a constitutional line to become cruel and unusual.

In early May, Indiana officials announced they would switch to Brevital – an alternative sedative.

Now, officials say they have enough Brevital on hand for the next execution, even though executives from its maker – Par Pharmaceutical – say they don’t want it used in that way. “The state of Indiana’s proposed use is contrary to our mission,” the company said in a statement.

Par Pharmaceutical went on to say the company is working with its partners to establish distribution controls on Brevital to “preclude wholesalers from accepting orders from departments of corrections.”

Similar problems have led officials in many states to remain mum about names of the drugs they use, an attempt to protect the companies that supply them.

“The difficulties that many states have had in finding the drugs necessary for lethal injections is a warning to states not currently carrying out executions that problems in this area are likely to arise,” said Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. “Each state carries out its own decision-making on issues such as the death penalty.”

And those decisions have become more complicated. The Pew Research Center has found that a majority of Americans still favor the death penalty but the margin has been shrinking. A 2013 Pew survey found 55 percent of Americans said they favor the death penalty for convicted murders, the lowest level of support in the past two decades. Twenty-five years ago, that number was 78 percent.

The reasons for shifting opinions are varied, but they include publicity about cases in which inmates have been found innocent.

“The number of exonerations from death row has had a profound effect on states considering whether to abolish the death penalty,” Dieter said. “Even if a state has not had a serious miscarriage of justice in this area, they can see that such mistakes can happen based on evidence from other states.”

The death penalty is also expensive. According to the Legislative Services Agency, simply trying a death penalty case in Indiana costs an average of $449,887. Meanwhile, the average cost for a case resulting in life without parole is $42,658.

Thirty-two states still have the death penalty on their books. Of the 18 without it, three have abolished executions since 2000.

Indiana currently has 13 inmates waiting on death row, with many having been there for more than a decade. All still have appeals left.

All were convicted of murder. But to receive the death penalty, a prosecutor must also prove one of 16 aggravating circumstances. The most common is the commission of another serious felony, such as rape or attempted murder, at the time of the original offense.

Other aggravating circumstances include a defendant’s lack of remorse and his or her criminal record.

Once convicted, an inmate has a number of appeals available and can be represented by the Indiana Public Defenders Council. Once those appeals are exhausted, an execution date is set and the inmate will be escorted to a separate holding cell where he or she can have more visits.

The inmate also has the option of having a final meal prepared for them. “Some ask for it, some don’t,” Garrison said.

While being transported to the execution chamber, the inmate will be put on a gurney with lines placed in his or her veins.

Witnesses may be allowed, depending on whether the inmate wants them. Witnesses are limited to the warden and assistants, prison chaplain, two physicians, five guests, and a spiritual advisor, along with eight adult family members.

The Department of Corrections – which perform the execution and practices the lethal injection process once every quarter – will establish a support room for the victim’s family, upon request.

The procedure for administering the state’s three-drug protocol will then begin, just after midnight.

The first drug – Brevital, sodium thiopental or another sedative – will then be administered, which is meant to force deep and painless unconsciousness. The second one stops the respiratory system and the third stops the heart.

But the process doesn’t always go so smoothly.

Joseph Wood – executed earlier this year in Arizona – took almost two hours to die by lethal injection. He was injected with an “experimental” cocktail. His lawyers said the execution was illegal due to its cruel and unusual punishment.

Arizona Governor Jan Brewer said the execution was legal.

Dennis McGuire – an inmate on Ohio’s death row – was given the same cocktail of drugs and took 30 minutes to die, an execution that defense attorney Allen Bohnert deemed as a “failed, agonizing experiment.”

In April, Clayton Lockett – a death row inmate in Oklahoma – reportedly appeared to regain consciousness after the drugs had been administered. He later died of a heart attack.

Seth Morin is a reporter for TheStatehouseFile.com, a news website powered by Franklin College journalism students.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Programs

View More Programs

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.