Over the course of his long and distinguished writing career, Peter Matthiessen — who died this past weekend at the age of 86 — chased numerous demons, from Florida outlaws to missionaries and mercenaries in South America. In his latest novel, which the ailing writer suggested would be his last, takes us back to a week-long conference held at Auschwitz in 1996. Here, as autumn shifts toward winter, Jews and Germans, Poles and Americans, rabbis, Buddhists, European nuns and slightly crazed survivors of Nazi genocide stand witness to the atrocities of some of the greatest demons of history.

Because of the subject matter a novel like this is difficult to read and devilishly difficult write. How does a writer choose to portray this material? By focusing on the murderous history of the place? Or by pulling back and surveying such monstrousness from the distance of the moon?

Matthiessen overcomes these problems with a deft act of craft. He invents a Polish American academic named Clements Olin to guide readers among the various points of view, some more hysterical than others. At first, Olin seems to be among the least involved of those participants who have come here to bear witness, especially since he doesn't even like that phrase — he finds it anachronistic and over-earnest. "Excepting the few elderly survivors among them, what meaningful witness can any of them bear so many years after the fact? Witness to what, exactly? ... Their mission, here however well-intended, is little more than a parting wave to a ghostly horror already withdrawing into myth."

As we might expect, the event itself is filled with ecumenical misunderstanding: Germans in the conference group certainly carry guilt, and the Israelis bear a certain amount of bad will toward the Germans. The Polish priest seems on the verge of a breakdown, which makes sense given Poland's own role in the destruction of European Jewry. The nuns seem the least compromised among the participants, but one young acolyte, Sister Catherine, becomes involved in a flirtation with Olin, the American academic, and lives through the second half of the novel on the edge of compromise. As the possibility for passion deepens on the American's side, we learn that he has more heart than we first might have considered. And more than an abstract reason for attending the conference.

As it happens, Olin has deep family ties to the nearby town of Oswiecim, the place where, as one woman from the conference murmurs, "a faint odor of burning flesh still lingers here a half century later." A photograph he carries, of a young woman from the town, certainly suggests that the supposedly objective academic Olin has secretly been carrying a lot more weight than we first recognize. Coming upon the camp's crematorium he suffers a vision and nearly breaks down: "The iron door, slamming, smashes feet and clawing fingers. A crack of light as, jammed by arms, the door reopens for a moment, is slammed again and bolted — that clang perhaps the signal to executioners overhead peeping filthily as demons as they seed the pandemonium below with white cyanide pellets dumped from orange-and-black canisters."

In this place of horrors all the participants, Olin among them, feel the desire for some kind of human attachment. So much so that one night after dinner, they stand and slowly form a chain that moves in a dance onto the small stage and off again. Olin is baffled — it's not the kind of thing he'd normally do. But eventually his bafflement "metamorphosed into gentle rejoicing, transcending the atmosphere of grief and banishing lamentation from the hall ... What could there be to celebrate in such a place? Who cares? He is delighted to be caught up in it." He takes Sister Catherine's hand and keeps moving.

As does the novel, moving the characters toward the end of their gathering, and possibly toward some kind of leap of self-understanding. Even as a reader understands this, the title returns to haunt us. Paradise? Where? How? In this place?

And the answer comes back as if in some Buddhist conundrum. Here, now, yes, demons and all.

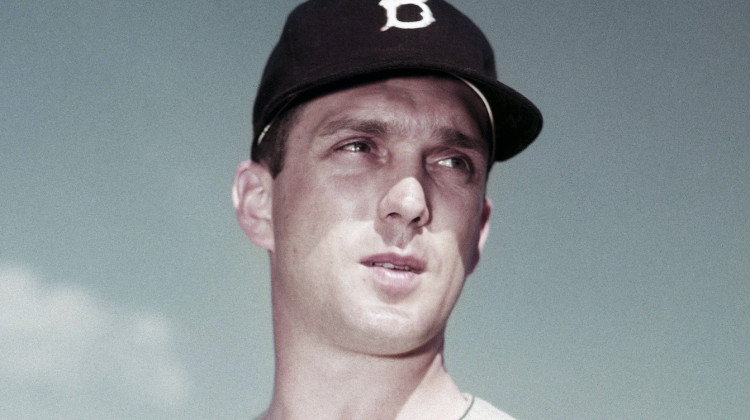

Peter Matthiessen, 1927-2014: Rest in Peace.

9(MDEwMDc1MzM3MDEzNDczOTA0MDc1MzViMQ001))

DONATE

DONATE

View More Programs

View More Programs

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.