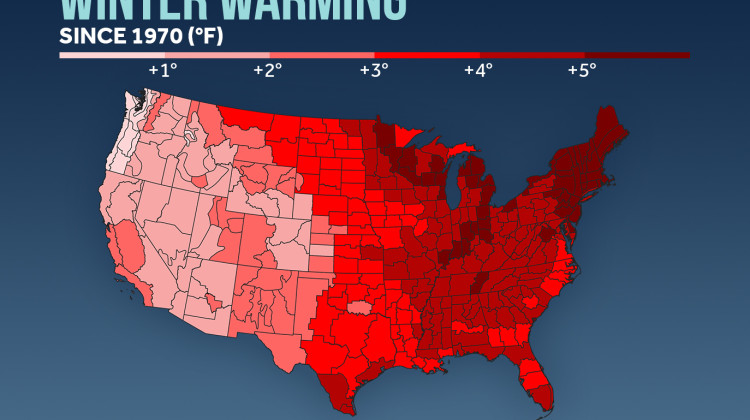

Climate Central, an independent research and reporting collaboration, reports the average winter temperature has gone up by between 4 and 5 degrees in Indiana from 1970 to 2023.

Courtesy of Climate CentralClimate change isn’t playing out everywhere in the same way. That’s because our climate is different from other parts of the country and the world, and that can make data confusing. A member of our audience from Noblesville wanted to better understand it.

Melissa Widhalm is the regional climatologist and associate director at the Midwestern Regional Climate Center at Purdue University.

She said scientists often look at the whole globe to get a more reliable picture of climate change because there’s less variation.

“So if I'm talking about Earth's temperature over a year — that's a very stable measurement. You can think of it a lot like our bodies. If we look at it from year to year, it doesn't fluctuate very much. Just like our body temperature really only operates in a small window of temperatures before we feel like we have a fever or we're too cold and we start shivering. That's similar to how the Earth's global temperature is,” Widhalm said.

Of course, many Hoosiers want to know how climate change affects them specifically. After all, hurricanes, wildfires and sea level rise aren’t something we often experience here.

Widhalm said if you want to get a better idea of how climate change is playing out in Indiana, there are some key indicators you might want to watch. She also offered advice on where to find accurate information about them.

Indiana climate indicator #1: Nighttime low temperatures are rising

Widhalm said Indiana hasn’t seen the brutal heat waves people in the southern or northwestern U.S. have experienced over the past couple of decades. What we have seen is that nighttime low temperatures are warming much faster than any other temperature measurement in Indiana — including highs and average temperatures.

While some Hoosiers might not mind those warmer nighttime temperatures in the winter or fall, they can be deadly in the summer.

“You think back to the heat wave of 1995 in the Midwest: we got really, really high in the daytime — but what was really damaging and killed hundreds of people was the lack of relief overnight. So you had really high temperatures, you had high humidity and that moisture in the air would not let the temperature cool down at night,” Widhalm said.

This is especially dangerous for Hoosiers who don’t have air conditioning or live in apartments with little airflow.

Widhalm recommends looking at NOAA’s Climate At A Glance resource to find accurate info about nighttime lows.

Indiana climate indicator #2: The date of the first “hard freeze” is moving

The National Weather Service considers a “hard freeze” to be possible when temperatures dip below 28 degrees Fahrenheit. This can be an important date for gardeners and farmers in particular, but it has implications for all Hoosiers.

Ticks and mosquitoes are less likely to go dormant or die off without a hard freeze or two. Plants that produce pollen can stick around longer also — which Widhalm said can extend the allergy season. Widhalm sees this firsthand since one of her kids suffers from seasonal allergies.

“It is not until we have many hard freezes in the fall that we can take him off his medicine. If we take him off too soon, symptoms come back,” she said. “We used to take him off before Thanksgiving. We can't take him off until early December now, because we're just seeing that a little bit later, year after year.”

Widhalm recommends looking at the Freeze Date Tool — a collaboration between the Midwestern Regional Climate Center and USDA Midwest Climate Hub — to track freeze date trends.

Indiana climate indicator #3: Annual rainfall is going up

Widhalm said Indiana has seen a notable upward trend in annual rainfall over the past 125 years. She said rainfall is going up in every season in the state, but some of the biggest increases in the future are expected between November and April.

“Which is bad because that's a time of year when we really don't need the water. We're already pretty wet. Could have issues with flood control, you could have issues with soil erosion. Just all sorts of problems that stem from getting too much water when you don't need it,” Widhalm said.

Widhalm said NOAA’s Climate At A Glance resource has info on rainfall trends and so does Purdue University’s self-service data portal. The portal does require you to sign up, but an account is free.

Indiana climate indicator #4: Heavy rain events are becoming more frequent and more extreme

That rainfall isn’t just going to get more frequent — Widhalm said we’re also going to see more heavy rain events. These are the kinds of heavy rains that can lead to flooding — and not just in areas near rivers and lakes. When all of that rain hits hard surfaces like roads and sidewalks, that can lead to flash flooding.

Widhalm said the Midwest and the Northeast are two places in the U.S that have seen the largest increases in heavy rainfall events — and Indiana will have to find ways to deal with them.

“Where are we going to put all this water when it comes down so quickly? How are we going to build our pipes to withstand a large volume of water, so it doesn't flood people's basements or major intersections or damage bridges?” she said.

The 5th National Climate Assessment shows how these heavy rain events are already playing out in the U.S.

How many years of data should I look at?

Climate is the long-term pattern of weather over time. So how much time you’re looking at matters a great deal. Widhalm said it’s good to have at least 30 years of data if not more.

“Because with 30 years, we feel pretty confident we're getting a pretty reasonable range of conditions. And since we're working on averages, we're sort of smoothing out those highs and lows to give us a benchmark of our climate,” she said.

However, if you’re looking at extremes — like extreme high or low temperatures, for example — you’ll want as much data as possible.

“Because the nature of an extreme is, it's a rare event. It doesn't happen very often. And so if you want to know something about the heaviest rainfall events in your community, 30 years might not be enough to tell you your highest highs and your lowest lows. You might need to have a bigger sample of the record,” Widhalm said.

Finding credible sources on climate change

Widhalm said there’s a lot of misinformation out there — some of it is intentionally misleading and some of it simply misinterprets the data. So she said it’s important to know who is providing the maps and charts you’re looking at and understand what information is being shown.

“If somebody says ‘temperature.’ Well, are you talking about high temperature or low temperature? Are you talking about average temperature? Are you talking about for the whole year or for just a season? So really understanding what it is you're looking at, where it came from and when you're not sure, don't be afraid to reach out to an expert,” Widhalm said.

Widhalm said the Indiana State Climate Office and the Midwestern Regional Climate Center at Purdue University are happy to help answer questions or direct you to someone who can answer them. Both organizations also have a lot of tools and resources on their websites.

Join the conversation and sign up for the Indiana Two-Way. Text "Indiana" to 765-275-1120. Your comments and questions in response to our weekly text help us find the answers you need on climate solutions and climate change at ipbs.org/climatequestions.

Widhalm also suggests looking at the indicators platform of the U.S. Global Change Research Program and the NOAA Great Lakes Integrated Science and Assessment (GLISA).

In addition to those resources, we also recommend looking at reports from the nonprofit research group First Street Foundation — which shows risks from things like flooding, heat, wildfires, and extreme wind events. Climate Central — an independent climate research and reporting collaboration — also has several graphics that help show climate change in the U.S. and in select cities in a way that’s easy to understand.

Rebecca is our energy and environment reporter. Contact her at rthiele@iu.edu or follow her on Twitter at @beckythiele.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.