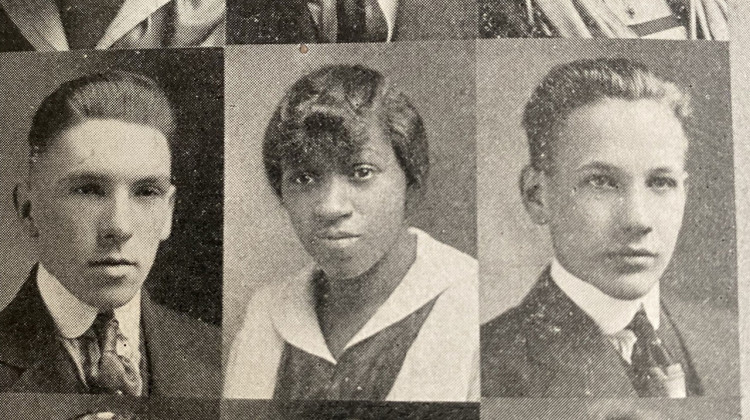

A photo of Bessie Speights' yearbook photo from 1916. Speights graduated from Arsenal Tech High School that year.

(Dylan Peers McCoy/WFYI)Randy Wilson was rummaging around a local flea market when he stumbled across a pristine yearbook from his old Indianapolis high school. From there, he started a collection that became a trove of history on Arsenal Technical High School and its graduates.

It was in the pages of one of those yearbooks that Wilson, 69, learned about Bessie Alethia Anderson Speights, who he believes was the first Black woman to graduate from Tech in 1916, just four years after the school opened. She went on to teach in Indianapolis Public Schools for 35 years.

“For her to do what she did was really a big accomplishment,” Wilson said. “She had to have some determination.”

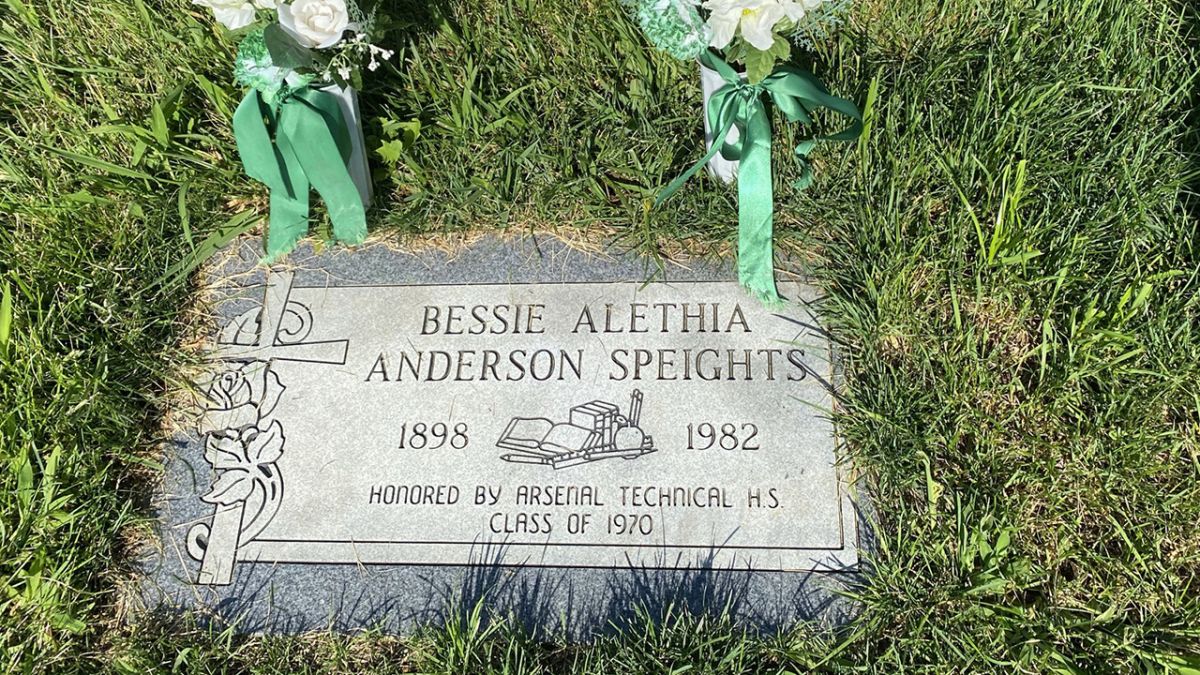

Speights' story gained attention this spring because Wilson spearheaded a campaign to place a headstone on her grave, which had been unmarked since her death in 1982.

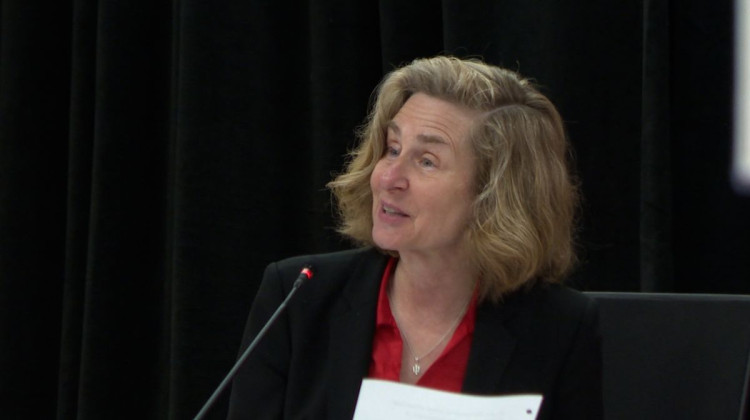

The interest in Speights story comes at a time when IPS leaders say that to improve education for Black and Brown students — who now make up more than 70 percent of the district — the community needs to talk openly about race. Students must learn Black history that goes beyond slavery, said Patricia Payne, the IPS director of racial equity.

“It's extremely important that children know about people like Bessie Speights and the challenges that she must have faced as a Black woman,” she said.

Speights' story as one of the earliest Black graduates of Tech was unknown until Wilson’s research.

After he saw her photo in the yearbook, he used his background in genealogy to sketch an outline of her life. She was from Kentucky, and her parents were born during the Civil War. Her father was a sharecropper. It was a practice where tenant farmers, who were often Black, were in perpetual debt, owing a portion of the crops they farmed to the property owners.

“It was not slavery but it wasn’t much above slavery,” Wilson said.

Speights father died when she was a child, and the family moved to Indianapolis. Her mother was a cook in a restaurant and her sisters worked as a cook and a servant, according to Wilson’s research.

Tech was a primarily white high school when Speights enrolled. She was admitted long before 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court established racial segregation in public schools as unconstitutional, for a simple reason: Black students were entitled to an education under Indiana law. And Indianapolis didn’t have any segregated high schools for them to attend.

“I can’t even imagine what she must have gone through,” Payne said. “She was going to school at a time when racism was thriving. Whatever was going on though she did not let that deter her.”

The integration of Indianapolis high schools was fleeting. IPS opened a high school for Black students in 1927, Crispus Attucks, and the district banned them from Tech and other white schools. The school only began to educate Black students again around 1950.

After Speights graduated from Tech, she attended a two-year teacher preparation program and got a job in IPS. Along the way, she earned a bachelor's degree from Butler University.

For more than three decades, Speights taught in School 37 in Martindale-Brightwood, a segregated elementary school for Black children that has since closed. An Indianapolis Recorder article published when she retired said Speights was known for her work as a special education teacher.

Speights’ story captivated Wilson for years. When he first researched her life for an alumni website more than a decade ago, he learned where she was buried from the cemetery. But her gravesite was unmarked.

“It was kind of heart-rending to me at the time,” Wilson said. “About every other year I would drive out to the cemetery to see if anything had been placed on it and it hadn’t.”

Eventually, Wilson came up with an idea to memorialize Speights. He persuaded his graduating class that for its 50th reunion, it should place a marker on Speights’ grave. The alumni also created a scholarship in her honor.

This spring, the Tech class of 1970 unveiled the new gravemarker. It is a flat granite slub tucked in the grass. Engraved with books, pencils, and an apple to honor her career as a teacher, the marker has a note at the bottom that it was placed by Tech alumni.

It is a quiet invitation for observers to learn more.

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @dylanpmccoy.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.