Christian Cooper greets his mom Stephanie right after arriving home in Kouts on Monday, May 2, 2022.

Dylan Peers McCoy / WFYIJoe Cooper was afraid to send his 16-year-old son back to the local public school for students with significant disabilities.

Cooper and his wife withdrew their son Christian, who has autism, from the school the year before. They were worried about short staffing and cuts to his services.

So this time around, Cooper made an unusual decision. He took leave from his job as a heavy equipment operator — which offers benefits and pay close to $50 per hour — to work at his son’s school.

As a special education teaching aide, he earns about $17 per hour. That’s a “huge financial hardship” for their family, Cooper said. But in a special education system that Cooper sees as broken, it felt like the best way to help his son.

“We're failing these kids and this staff and these teachers,” Cooper said. “I think a lot of parents would do exactly what I did, but I don't think a lot of parents would be in a position to do what I did.”

The Coopers live in Porter County, a northern Indiana community where the special education system has faced intense criticism from parents. WFYI spent months investigating that system and spoke with more than two dozen parents, educators and advocates. Those interviews uncovered challenges students and families face in the Porter County public education system — including conflicts with school staff over special education services and safety concerns due to dire staffing shortages. They also revealed the lengths that parents will go to get an education for their children.

Christian Cooper is an affectionate and happy teenager. He likes to play outside, jump on the trampoline and watch Elmo videos on YouTube. But he can’t button his own shirt, or independently use a fork or pencil.

Because of those challenges, the local schools placed him at the Special Education Learning Facility, or SELF, a segregated building for children receiving special education. It’s a public school that Christian’s parents and others say can feel like an afterthought in a county with a reputation for high-performing suburban schools.

The Coopers want something simple — a good education for their son. They don’t care how the school system does it.

Many experts, however, say it is harmful to isolate children with disabilities away from the rest of the student population.

"If I had a magic wand, I would suggest that a facility like that should not exist,” said Martin Agran, a special education expert and emeritus professor at the University of Wyoming. “You have a situation that is almost beyond repair.”

Overall, leaders in Porter County Education Services deny that the problems are as severe as critics say, and they have made recent changes to special education in the county, including increasing pay for some educators.

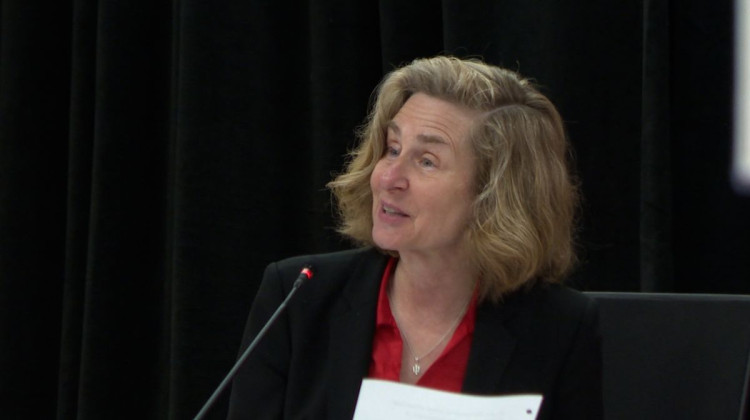

Executive director of special education Sandy Bodnar declined to answer questions about Christian Cooper, citing student privacy laws.

Bodnar describes SELF as “part of the continuum of special education services that provides students with the least restrictive environment to meet their individual needs.” She also cited a state regulation that requires school systems to make separate public or private schools available as options for students.

The origins of SELF go back to a time when children with significant disabilities were often turned away from public schools. Today public schools are legally required to teach children with disabilities. And under federal law, students in special education are supposed to be educated in the least restrictive environment appropriate.

That means they should learn alongside children without disabilities whenever possible. Experts refer to it as inclusive education.

And many researchers like Agran, who focuses on education for students with extensive support needs, point to evidence that inclusive education has academic and social benefits.

But districts continue to place children with extensive support needs in isolated programs where they don’t interact with their peers in general education. Nationally, public districts paid for about 166,000 students with disabilities to attend separate schools, according to the latest federal data. About 1,400 of those children are in Indiana.

"We have been fighting this fight in terms of integration for now close to 50 years,” Agran said. "It's been a national challenge."

The origin of the separate school — and its alternatives

American children with disabilities didn’t always have a right to an education. A Congressional investigation estimated that in 1972, one in five students with disabilities were not in school at all.

In the mid-1900s, families of children with disabilities didn’t have many options, said historian Robert Osgood, an expert on special education who has written about Indiana. They could send their children to overcrowded residential facilities which did little to prepare residents for life. Or they could keep them at home.

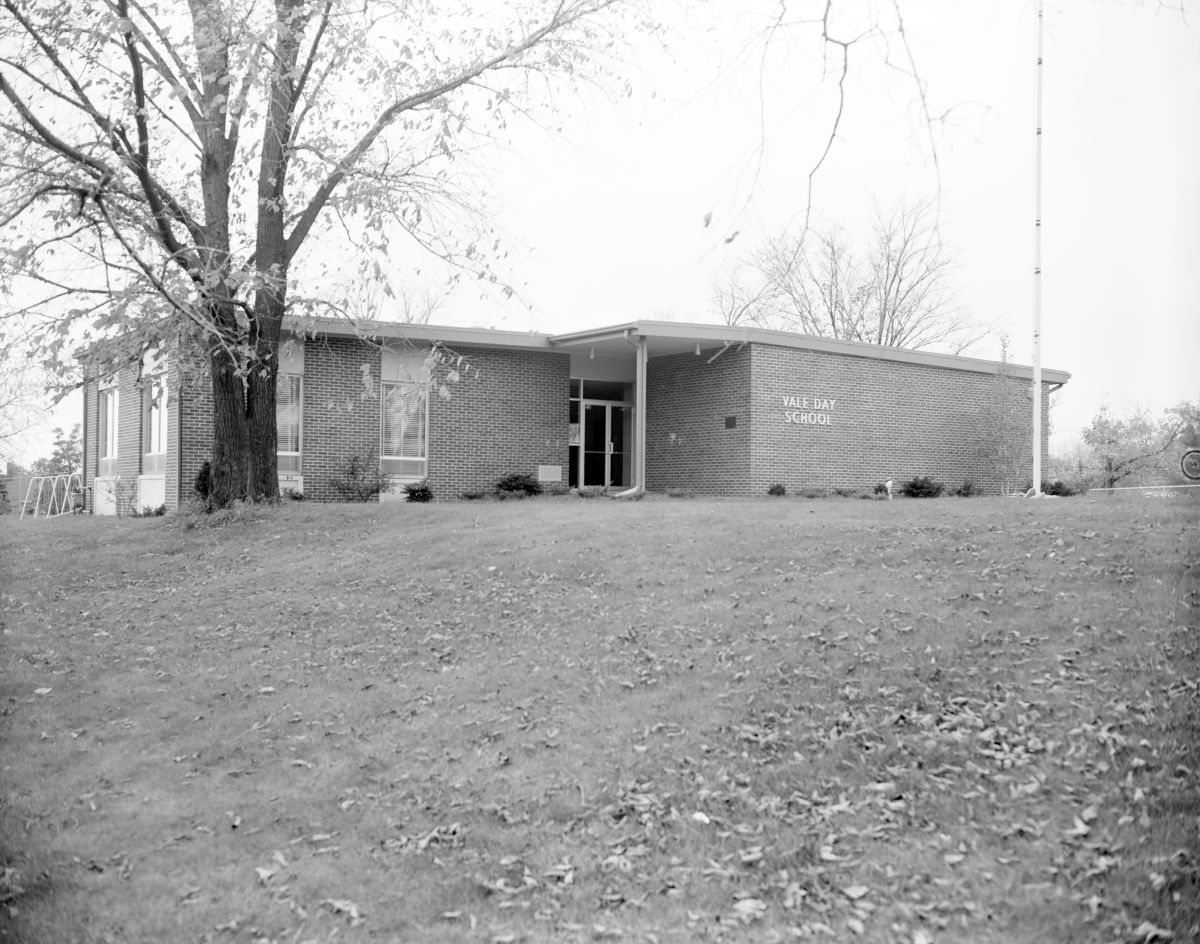

As parents started to see the value of education for children with significant disabilities, they began to open up private schools, Osgood said. In Porter County, residents opened a private school called the Vale Day School in the 1950s, according to the Vidette-Messenger, a Porter County newspaper.

In the 1960s and 1970s, parents pushed states to expand public school access for children with disabilities and won landmark court victories. In 1975, Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which entitled children with disabilities to a free, appropriate education in public schools.

“It made it very clear that from a federal perspective, schools had to admit kids with disabilities — they couldn't just shove them off to the side,” Osgood said.

Public school districts in Porter County formed a cooperative to provide special education services, according to the Vidette-Messenger. In 1977, that cooperative moved the Vale Day School to a new building called the Special Education Learning Facility, or SELF.

In the following decades, a national political movement for inclusive education gained momentum, according to Osgood’s book, “the History of Inclusion in the United States.” Families and people with disabilities argued that just as racial segregation is morally wrong, it’s unjust to segregate students with disabilities. By the mid-1980s, some advocates were calling for all students to be taught together.

Academics who study students with extensive support needs overwhelmingly believe that inclusion is better in most cases, pointing to evidence that instruction is more rigorous and students benefit from exposure to children without disabilities.

Agran, the expert from University of Wyoming, said that inclusive classrooms can take many forms – such as a co-teaching model where general and special education teachers work together, or an approach where students work in groups.

Overall, he said, for inclusion to succeed, educators must match instruction to the needs of individual students. In a class on geography where most students are learning state capitals, for example, a student with extensive support needs might instead focus on learning where she lives. “It would still be an Indiana-based geographic skill,” he said.

Parents have few options

For many families, however, inclusive education isn’t an option.

Joe Cooper and his wife Stephanie have been concerned about Porter County’s special education services for more than a decade. Sitting at their dining room table for an interview with WFYI in the spring of 2022, Stephanie Cooper recalled the moment she realized the school was failing her son.

During a tour of Christian’s preschool classroom, he brought her to the spot where he usually sat — a small chair with an attached desk that forced him to stay in the seat. Stephanie Cooper said it was a restraint chair that educators used nearly every day to keep Christian from moving around the room.

“After that, it was over for me,” she said. She told her husband, “What's he learning? Nothing. He's not learning anything. He learns that ‘I sit in this chair, and then they give me all this stuff that I don't understand.’”

When asked if staff currently use restraint chairs, Bodnar, the executive director of special education for Porter County Education Services, said in an email that “current protocol at SELF School prohibits the use of restraint chairs” and pointed to the district seclusion and restraint policy.

Bodnar did not respond to a question about whether SELF used restraint chairs at the time when Christian was in preschool. WFYI spoke with another parent whose child attended SELF preschool near the same time as Christian, and she also said the school used a restraint chair to control her son.

Researchers who are critical of the focus on inclusive education argue that the quality of instruction is more important than the type of placement. In some ways, Christian’s parents agree.

After they learned he was regularly restrained, the Coopers decided to leave SELF. They enrolled him in autism treatment, which they say was paid for by their medical insurance. It was also a segregated setting. But the Coopers say the center was high-quality, and Christian learned to use some signs and pictures to communicate.

Traveling to and from the center, however, took more than two hours each day. After years of making the commute, the Coopers decided to return to public school, where Christian could ride a bus.

For the Coopers, that meant returning to SELF. The family lives in a rural community, and their school district — East Porter County Schools — is part of Porter County Education Services, which runs SELF.

In a 2022 education plan for Christian Cooper, staff with the Porter County special education system wrote that he should be educated at SELF because “a community school with a specialized program would not provide enough support at this time as he has high educational needs.”

Staff also wrote that Christian needs a small school environment that “is not available in his homeschool.” The rural school he would attend if he were not at SELF, however, is a combined middle and high school that educates only about 450 students.

When school seems like ‘babysitting’

The segregated setting of SELF doesn’t just isolate students with disabilities. Joe Cooper believes it isolates the entire school because no single district is responsible for it. Rather, SELF is run by Porter County Education Services, which is overseen by a board made up of the seven local superintendents.

The setup makes it easy for participating districts to neglect the problems at SELF, Cooper said. Ultimately, he believes the system has never provided the education Christian is entitled to under the law.

“It's been babysitting. That's all it's ever been,” Cooper said.

Speech therapists work with Christian — who does not speak — on communication skills like sign language and using pictures. But he only receives 30 minutes of speech therapy each week.

The Coopers want school to help Christian with basic skills, like eating, buttoning clothes and holding a pencil. But the school cut his regular occupational therapy, which might have helped with those skills.

“What that says to me is they just don't have the staff and they want to take him off their caseload, honestly,” Stephanie Cooper said. “He can't do everyday needs on his own.”

In an interview last year, Bodnar said decisions about student therapy were made on a case-by-case basis with parent involvement, and “if a student no longer received occupational therapy, it's because there was probably an evaluation done, the student no longer needed it.”

In response to a follow up email in October, Bodnar said the school system has not cut occupational therapy for students because of staffing shortages.

The Coopers responded to the problems with Porter County schools by withdrawing Christian and placing him in autism-therapy for a second time in 2022.

The Coopers have tried to push the school system to improve. Stephanie Cooper helped found a parent teacher organization at SELF. Joe Cooper ran unsuccessfully for a seat on the East Porter County Schools board, one of the seven districts that participate in Porter County Education Services.

Ultimately, autism therapy was only a temporary alternative. The treatment center had told the Coopers that Christian was too old to continue their program.

The family returned Christian to SELF yet again — and Joe Cooper decided he wanted to be in the same building as his son.

When WFYI spoke with Cooper last month, he said he was working as a teaching aide at the school. He expected it to be temporary. But five months after he started, he’s still there.

He felt like all of the students — not just his son — needed him. He’s not sure what he’ll do next.

Lee V. Gaines co-reported this story.

Eric Weddle edited this story for broadcast and digital.

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.