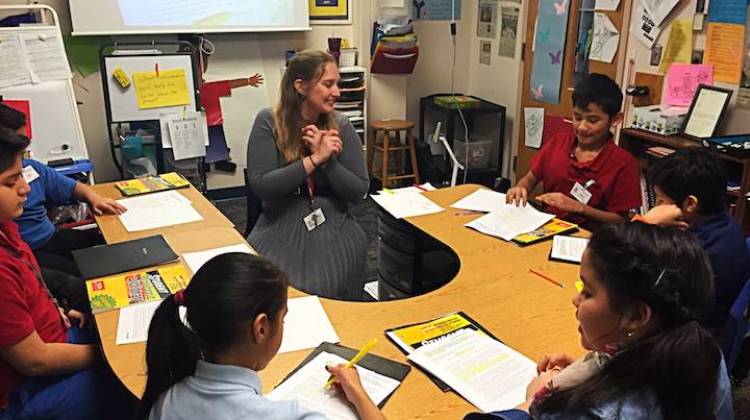

Melissa Mitchell teaches an English lesson to a group of fifth graders at West Goshen Elementary School. 51 percent of students in the Goshen Community School Corporation are Latino, and a quarter of students need English language services at school.

Claire McInerny/Indiana Public BroadcastingJerry Hawkins was in the car with his wife when he got his first good look at the budget cuts.

“She could see the look on my face when I started seeing some of the numbers,” Hawkins says. “It was difficult. I didn’t sleep real well knowing the severity of the situation.”

Hawkins is Director of Finance for the public schools of Goshen, Indiana.

Until recently, the state sent extra money to schools like Goshen’s that educate large populations of disadvantaged kids, including those living in poverty, receiving special education services or learning English as a second language.

More than half of the students in Goshen are Latino, the highest concentration of any district in Indiana. And many of those students depend on the district’s special English Language (EL) program. But it’s costly –an expense that many other schools in the state simply don’t have.

Last year, Indiana lawmakers rewrote the rules for how they give money to their public schools. Specifically they voted to cut down on the extra money sent to places like Goshen and to fund districts equally, whether they’re in an affluent suburb or a high-poverty district.

Republican leaders who wrote the budget say they wanted school funding to be equal, regardless of student make up in a district. During the session last year, Rep. Tim Brown, R-Crawfordsville, said issues of poverty should not dictate how the state gives school districts money.

“Did Mary’s mother get arrested the night before? Did Johnny not come with shoes to school?” Brown says. “Those to me are not core issues of education.”

For Hawkins, the move has meant a loss of some $3 million, roughly a third of the money he uses to fund Goshen’s EL program, which includes additional teachers, teaching assistants, counselors, and considerable parent outreach.

In School Funding, What is Equal?

Goshen has changed a lot. In recent decades, manufacturing jobs here have brought more Spanish-speaking families to the small, northern Indiana town. And those changing demographics have forced Goshen’s schools to make teaching non-native English speakers a top priority.

Among the students benefiting from Goshen’s EL program is Hector, a fifth-grader at West Goshen Elementary. He says his special, English-language class is his favorite.

“It’s much easier in here to speak than back in our [traditional] classroom because over there you’re sort of shy if you mess up on a word,” he says. “But here it’s safer.”

When kids like Hector feel safer in class, they perform better, too. That’s one reason Superintendent Diane Woodworth says test scores went up, not down, as the number of low-income, Latino students increased in Goshen.

Woodworth says lawmakers and other Indiana communities should pay attention to what Goshen has accomplished with that extra money.

“I think that we are a microcosm of the real world,” Woodworth says. “I think if you look at the demographics of our country and of our world actually, more and more places around the world are just melting pots.”

But, she worries, it will be tough for Goshen to maintain success with less money.

Hawkins, the finance director, worries that this cut in the name of fairness is fundamentally unfair.

“That’s fair if everyone’s on the same playing field,” Hawkins says. “We’re on a different playing field than virtually anyone else in the state.”

Fortunately, the district has some cash in reserve, but, when that runs out in a few years, many in Goshen say the schools’ EL program won’t be able to keep pace with the growth in Latino students.

Hector says his whole family benefits from his English lessons at school.

“My dad mostly uses me as a translator to help him with other words that he doesn’t know in English,” he says. “Like at church, stores, or when they send him a message on the phone about something.”

Can Superintendant Woodworth imagine a day when she’ll have to scale back the district’s EL program?

“We’re not going to go there, because we’ll find money,” she says. “I’m an eternal optimist…but we’ll look for grants. I think we can convince people to give us money because we’re doing good things here.”

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.