Racial minorities and rural populations in Indiana were hit harder by COVID-19 than the overall population. That’s according to the largest study of its kind to date carried out by the Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health.

Racial minorities and rural populations in Indiana were hit harder by COVID-19 than the overall population. That’s according to the largest study of its kind to date carried out by the Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health.

The study looked at nearly 2 million adult residents tested for COVID-19 in Indiana between March 2020 and December 2020. The goal was to identify the communities that need the most public health intervention and support during and after the pandemic.

The data showed that race and geography played a role in a person’s risk and health outcomes after exposure to COVID-19.

“A lot of other studies that have been within a hospital, for example, [looking at] all the patients that came to one medical center or all the patients who came to one clinic, [and some] showed similar patterns in terms of disparities, particularly among Black populations, and even some in the rural areas,” Brian Dixon, the lead author and director of health informatics at the Regenstrief Institute, said.

This study analyzed data from the Indiana Network for Patient Care, which has information from 38 distinct health systems representing more than 100 hospitals, labs and clinics across the state.

“There's lots of numbers that are on different dashboards,” Dixon said. “But what we did was we normalized those data so it can then be compared to the U.S., to other countries, to other areas, to different time points.”

The study shows COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and death rates per 100,000 people in each demographic group, making it easier to compare when similar large-scale studies are conducted in different places.

Systemic Barriers, Politics And Health Care Deserts

When it comes to race, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders had a significantly higher infection, hospitalization and death rates — as much as six times higher compared to Whites.

While the data showed that Black Hoosiers were infected by the virus at rates rivaling White Hoosiers, they were nearly twice as likely to be hospitalized and 1.4 times more likely to die.

Systemic barriers to care, inability to work remotely and persistent health and socioeconomic disparities are to blame for the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial minorities, according to Dixon.

Significantly, those who define their race as “unknown” or “other” have also seen a disproportionate impact compared to the overall population — death and hospitalization rates were more than two times higher than Whites.

The study said that “it is not unreasonable to assume that many Hispanics may be in that group as they may not wish to disclose demographic details”.

Geography also mattered. Hoosiers living in rural communities were more likely to die from COVID compared to urban populations.

During the first wave of the pandemic, rural communities did not see a big impact from the virus. In fact, during the period between March 2020 and April 2020, rural communities saw lower rates of infection, hospitalization and death. But as the virus continued to ravage communities across the country — particularly between September 2020 and December 2020 — rural communities’ rates of COVID infection, hospitalization and death surpassed urban communities and even many racial minority groups.

“And so initially, when COVID-19 hit urban areas, there was a statewide lockdown. There was a lot of emphasis on it,” Dixon said. “Then there were a lot of people in rural communities that said, ‘I don't think this is really happening in our community, right? It might be a hoax, it might not be real.’”

But rural communities eventually felt the brunt of the virus. Dixon said the reasons behind that delayed impact are a mix of politics, misinformation and a persistent shortage of health care providers per capita.

Rural Indiana communities are heavily Republican and overwhelmingly voted for former President Donald Trump during the last two presidential elections. They are more likely to be skeptical about COVID-19 mitigation and safety policies outlined by health authorities like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But that’s not all.

“[Rural] populations generally lack access to primary care and so, many of them have chronic conditions that might not be managed very well,” Dixon said. “So there are challenges with obesity or challenges with cardiovascular disease, there's challenges with diabetes in those communities. Then when those people get sick, they often end up in the hospital and they're sicker. And so there, they have challenges in recovering from diseases, including COVID-19.”

You Can’t Fix The Past, But Is The Future Any Brighter?

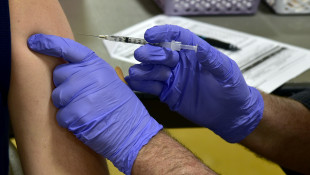

COVID-19 vaccination rates in rural communities remain low in Indiana. At the same time, many of those communities are fighting mask-mandates and other COVID safety policies in schools and other venues. All the while studies confirm that the delta variant is a lot more contagious than earlier variants. All this leaves rural communities in the midst of a perfect storm of contagion. And it makes public health experts like Dixon worried about what’s to come.

“So there's definitely a gap there between urban vaccinations and rural vaccinations. And there's a gap based on race as well,” he said.

“We see, for example, younger populations in the Black and Brown communities not getting vaccinated. Older populations in those communities, thankfully, are pretty well vaccinated, but the younger populations are not. And those are the people that we tend to see in the hospital right now, too, from the urban areas.”

As of now, looking at COVID trends across all phases of the pandemic in 2020, it seems that the gap between racial groups narrowed by the end of the year, especially as the burden shifted from urban to rural communities. But given the big proportion of the population that identifies their race as “unknown” or “other”, it is likely that the overall disparity is larger than what the data currently shows.

The long-term impact of COVID-19 infection is still not entirely clear. The populations hit the hardest by the virus may require more health care support to deal with persistent problems –– like headaches, fatigue, weakness and some serious neurological symptoms –– from COVID, known as “long-COVID”.

The economic fallout from the pandemic, which largely affected working-class Americans and communities of color, is another issue that could further exacerbate existing socioeconomic and health disparities unless a judicious recovery plan is put in place.

“You know, at this point in the pandemic, you can't go back and fix what happened last year, you can't fix really what's happening right now, where we see these same communities being hit hard again by COVID-19. But what you can do is you can work on recovery,” Dixon said.

This story was reported as part of a partnership between WFYI, Side Effects Public Media and the Indianapolis Recorder.Contact reporter Farah Yousry at fyousry@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @Farah_Yousrym.

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.