Indiana Department of Correction data shows the state now has more than 25,000 individuals in custody, with facilities operating at more than 95% capacity.

Džoko Stach / PixabayIndiana lawmakers heard stark warnings Thursday that the state’s prison population is again nearing capacity while funding for local alternatives is shrinking.

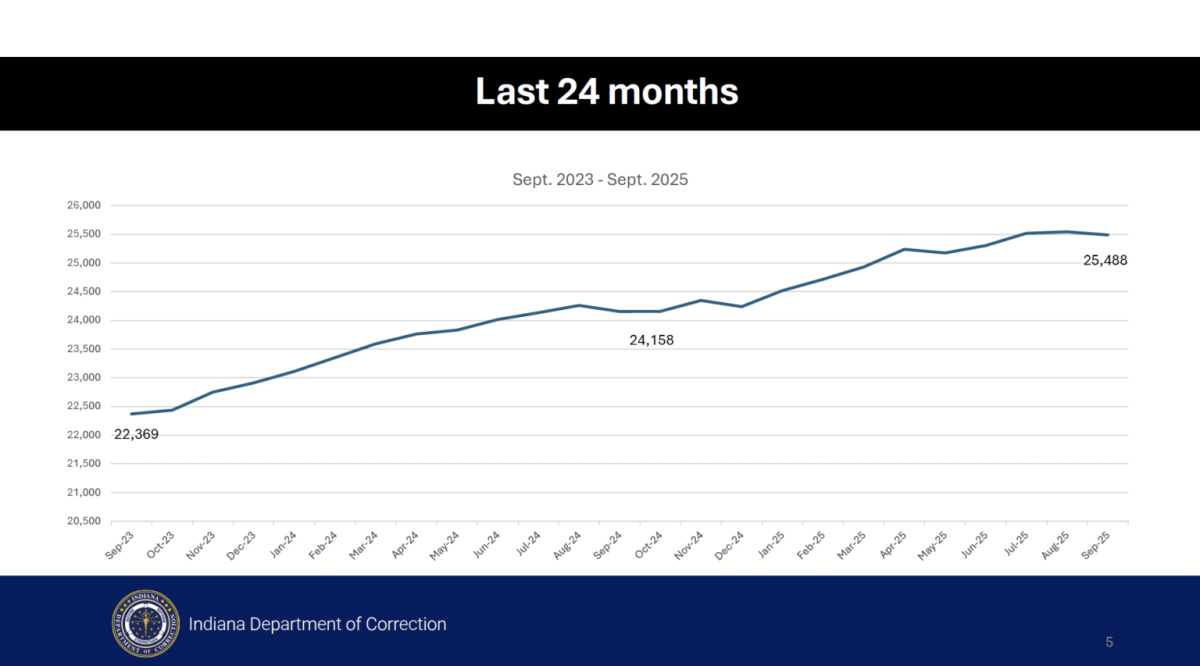

Margaux Auxier, with the Indiana Department of Correction, on Thursday told the state’s Interim Study Committee on Corrections that the agency’s incarcerated population dipped during the pandemic but is now back on the rise.

“We saw during COVID-19 that our numbers drastically dropped … our population did dip quite a bit during that time period,” she told the panel, which is made up of lawmakers, prosecutors, public defenders and other corrections-related officials.

She said DOC recorded 22,000 inmates at its low but that the state now has more than 25,000 individuals in custody, with facilities operating at more than 95% capacity.

Auxier told lawmakers that Indiana’s facilities are once again filling up.

“Now, we’re seeing an increase in our population overall,” she said. “To try to mitigate some of these issues, we have implemented a policy to allow more minimum security placements. We actually will eventually go onto a waitlist. So we’re trying to get those folks that are low-risk individuals into a facility that would help them transition better back into the community.”

Prison numbers rising

She noted that “an influx” of Level 6 offenders “are coming back to us to serve their time in DOC instead of at the county level.”

Auxier also pointed to sentencing changes as a factor behind the rise.

“If you think about it, just from a numbers perspective, 75% is more than 50% so they’re serving a longer period of incarceration,” she said, referring to changes in Indiana’s sentencing laws that increased the portion of a sentence that offenders must serve — from 50%, or day-for-day credit, to 75%, or three-for-one credit.

That change means offenders now serve a longer period of their sentence in prison, which Auxier said contributes to a higher prison population over time.

“Those individuals kind of stack up over time,” she continued. “That’s what we’re seeing as a stacking effect.”

Chris Daniels of the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council additionally highlighted a decade-long shift in criminal filings.

“We’ve seen a pretty dramatic increase in the most violent crimes, in our most serious levels, in terms of our murders and our level one and two felonies,” Daniels said.

“Our threes, fours and fives, they’ve stayed about the same,” he added, referring to felony offenders. “And then we see a decrease in some of our level sixes and a fairly significant drop in our misdemeanor charges.”

There are six felony levels with level one being the highest.

According to prosecutor data, Indiana courts handled 316 murder filings in 2015 compared to a projected 572 this year. Filings for the lowest-level offenses have moved in the opposite direction, with misdemeanors falling from more than 220,000 in 2015 to under 190,000 projected for 2025.

Story continues below.

Daniels said the complexity of those top-tier cases — murders, rapes and major drug-dealing prosecutions — has forced prosecutors to shift resources away from low-level filings.

“These are complex drug dealing cases, rape cases, terrible child molest cases, the types of stuff that we really want prosecutors’ offices focusing on,” Daniels said.

But Zach Stock with the Indiana Public Defender Council further noted that despite spikes in violent incidents, overall crime trends have been relatively flat or down.

“On average, crime is declining or holding steady, but there are spikes in certain places,” he said. He warned that “suicide, alcohol, drug-related deaths far outnumber homicides,” and that jails and prisons too often serve as “the providers of last resort” for behavioral health.

Funding shortfalls

Shifting gears, Scott Hohl, executive director of Marion County Community Corrections, told the interim committee that probation and community corrections now supervise more than 106,000 Hoosiers daily. But state grant funding — the primary support for such programs — has been flat for seven years and was cut by $7 million statewide this year, with more reductions expected in 2026.

“We are community supervision,” Hohl said. “We are more cost effective than having someone in a jail or prison, and the services that we provide then provide individuals an opportunity to get out of the system and hopefully avoid returning to the system.”

Local impacts of the cuts are already showing up in next year’s grant awards. Monroe County, for example, will lose funding for both its drug court and mental health court, according to DOC records presented to the committee.

Story continues below.

In Lake County, community corrections saw its award shrink by nearly $600,000, with reductions hitting its re-entry and veterans courts.

Smaller counties face similar challenges. Boone County lost support for jail treatment programming, while Dubois County’s request for expanded community supervision was pared back.

Hohl cautioned that the timing could not be worse.

“The need has never been greater,” he said. “Cutting these programs now will only push more people into already overcrowded jails and prisons.”

Still, Sen. Aaron Freeman, R-Indianapolis, raised questions about the program’s financial accountability. He pressed Hohl for specifics on how much of the program’s budget comes from state grants, county contributions and user fees. Freeman was especially concerned about the lack of data on how many participants are declared indigent and therefore do not pay for services.

“Only government can be so special as to tell me, ‘We have a funding problem. We have no idea how many people don’t pay for a service that they’re actually using, but I need more money from the state,’” Freeman said.

The senator acknowledged the challenges that come with collecting fees from participants, however, especially once debts are sent to collections.

“I mean, look, there is a finite amount of money. In my time in the General Assembly, the amount of money that the taxpayers give to government has almost doubled,” Freeman said. “I don’t know if that’s right or wrong. I’m just telling you it’s almost doubled.”

Rep. Matt Pierce, D-Bloomington, pressed lawmakers to confront the root causes of crime rather than only funding prisons.

“Most of the people we’re encountering in these programs, they either have substance use disorders or mental health issues or most of the time, both,” Pierce said. “Unless we start funding these programs to get at the underlying cause of crime, we’re going to continue to have our constituents frustrated. Why does this person keep coming back all the time? Why didn’t you just lock them up forever?”

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: info@indianacapitalchronicle.com.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.