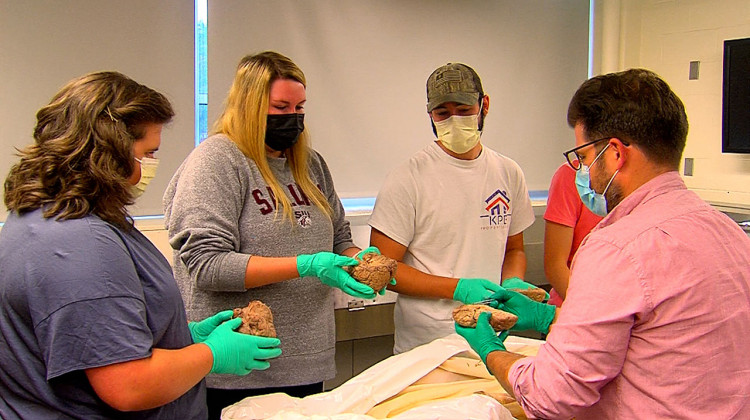

Medical students gather around their anatomy professor Jonathan Krimsier (right) as he talks about the different parts of the human brain. The students are enrolled in the Lincoln Scholars program at the SIU School of Medicine in Carbondale, Illinois.

(Benjy Jeffords/WSIU)Madison Funneman grew up in the rural Illinois town of Greenville, which has a population of about 6,000 people. So she’s seen the doctor shortage firsthand.

“You look around, there’s one hospital,” Funneman said. “Doctors are far and few [and] you can just tell … there’s such a high need for doctors in rural areas.”

It’s what made her want to go into medicine. Funneman is now a second-year medical student at the Southern Illinois University's School of Medicine in Carbondale, Illinois. She’s part of the school’s Lincoln Scholars program, which aims to train up-and-coming physicians to work in rural areas by providing them with rural clinical experience starting in year one.

In Illinois, rural communities have almost 50 percent fewer physicians per capita than urban areas. This follows national trends — across the U.S., rural communities face a shortage of physicians and other health care workers, which leaves people struggling to get the care they need.

While med school programs can’t fix the nation’s immediate health care staffing crisis, they can help boost the pipeline to ensure rural communities are better prepared.

Program Director Dr. Jennifer Rose said in some ways, the Lincoln Scholars haven’t been as impacted by COVID as students in other programs; the inaugural class started during the pandemic, so they’ve never experienced medical education in a non-pandemic setting.

“We'll see some impact for the better because these students at this stage have been tested in needing to be flexible and collaborative,” Rose said.

She said the pandemic has also given students opportunities to grapple with ethical questions usually posed as hypotheticals, like how to ration care when resources are scarce.

In rural America, health care shortages abound

Medical schools are often located in larger metropolitan areas, which is part of the reason it’s difficult to recruit physicians to rural communities, said former U.S. Health and Human Services Director Eric Hargan.

“People, if they're trained in a rural area, many times they stay there,” Hargan said. “But if you end up … sending them to a city to have them trained, they may start out in that city and they're kind of lost to the rural system.”

While attracting more specialists to work in rural areas is an important goal, it’s not always realistic, said Hargan, who is a native of Mounds, a small town at the southernmost tip of Illinois.

“I joke … you're never going to get 800 specialists to move to Mounds,” he said. “We're going to have to work on building out the workforce,” including nurses and other health care providers.

The Lincoln Scholars program was started to address the rural health care shortage, starting with physicians. Typically, medical students at Southern Illinois University spend one year at the school’s Carbondale campus in southern Illinois and move to Springfield, the capital city, to finish their training. But the Lincoln Scholars stay in southern Illinois for all four years, gaining rural clinical experience in nearby towns.

Rural doctor shortages are particularly stark when it comes to specialists, which means primary care doctors in rural areas need to be adaptable, able to fill in the gaps when specialists are either not available locally, or when patients are unable to access that specialized care elsewhere, Rose said.

On top of all those challenges, she said the job can be a bit lonely.

“It can be isolating to be a physician in a rural area,” Rose said. So it’s important for rural physicians to build a support network for themselves and know who to reach out to when working with patients with more complex health needs.

Training med students in rural areas — in the hopes that they’ll stay

Hands-on experience in rural clinics — right off the bat — gives med students in the Lincoln Scholars program opportunities to build their network and prepare for the challenges they will face after graduation. The students work with physicians and other health professionals in small towns across southern Illinois.

“We let them get here, figure out where the bathrooms are and they start delving into clinical medicine right away,” Rose said.

The kinds of problem-solving skills rural physicians need often go beyond medicine because of the many non-medical barriers to care, also known as social determinants of health.

For example, access to transportation is a major barrier for many rural patients, Rose said. And while telehealth has begun to help fill the gap, there are still many rural areas with limited access to broadband internet.

Funneman, the second-year student, said she chose Southern Illinois University for med school so she could stay close to home.

She said it was a bit intimidating at first, but she appreciates getting a head start on clinical work; most medical schools don’t begin clinical training until the third year.

“I started going to [a rural clinic in] Eldorado and working in a clinic and it was definitely nerve wracking because I'd never done anything like that before,” Funneman said. “My background was in research here, so I had never had any clinical experience.”

Students in the Lincoln Scholars program aren’t required to work in rural areas after they graduate. But the hope is that many of them will choose to stay.

Funneman said she plans to return to her hometown of Greenville after she graduates, and become a primary care doctor like her father.

“That community … shaped me and I want to give back to them the way that they gave to me,” she said. “That's the whole reason I'm doing this.”

WSIU’s Jennifer Fuller contributed reporting.

This story comes from a reporting collaboration that includes WSIU and Side Effects Public Media — a public health news initiative based at WFYI. Follow Steph on Twitter: @stephgwhiteside.

9(MDAyMzk1MzA4MDE2MjY3OTY1MjM5ZDJjYQ000))

DONATE

DONATE

View More Articles

View More Articles

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.