By Jennifer Delgadillo and Mary Claire Molloy

At an Indianapolis church parking lot, 38-year-old Juan prepared for an upcoming performance on Good Friday.

He wasn’t nervous to play the main part in the crucifixion story. A few dozen familiar faces made up the crowd, including his brother, dressed as Pontius Pilate, and his wife, who would be one of the weeping women of Galilee.

Throughout the practice, the group sang, “Perdona tu pueblo señor, perdona tu pueblo, perdonalo señor.”

Forgive us, your people, oh lord, forgive us, your people, forgive us holy lord.

Back in Juan’s birthplace of Michoacán, Mexico, they call the reenactment of the 14 Stations of the Cross by the Latin name, “Via Crucis.” Juan remembers participating as a teenager, but it wasn’t until he came to Indianapolis that he wore a crown of thorns.

It was an honor, Juan told Mirror Indy in Spanish, to be chosen to show people the suffering of Jesus.

And while the Via Crucis gives him hope, he understands he’s not immune from the forces making it more difficult to live with every passing day — pushing his wife, their children and the rest of his friends and family into the shadows.

Those forces include the Trump administration, which has ramped up deportations, broken up families and sent people to foreign prisons, sometimes without due process. Juan and Rosaura read the headlines about people disappearing from their communities.

“I’m worried they will take me away and separate me from my children,” Juan said.

New fears in an increasingly international city

Juan and Rosaura crossed 20 years ago, separately.

It was an American dream: They met 12 years ago while working at a bread factory. For a full year they were friends, before going on their first date.

While they are living in the U.S. without legal permission, their five children are U.S. citizens. Juan works in construction, while Rosaura is a stay-at-home mom and takes the family to The Children's Museum and the Indianapolis Zoo to watch the dolphin show.

She cooks fideo soup and pozole, but she also likes to make fried tilapia and spaghetti.

Together, they built a life here, joining a tight-knit community of Mexican immigrants adding their culture to the fabric of a city that’s no longer majority white.

Even in an increasingly international Indianapolis, the cultural influence of 30,000 Mexican immigrants stands out.

Just turn on the radio to 107.1, the city’s oldest Spanish language station. Or shop for tortillas at one of the many Morelos stores. Or grab a meal at one of the hundreds of Mexican restaurants and food trucks.

There’s spiritual nourishment here, too.

The first Spanish language mass in Indianapolis was officiated at St. Mary's Catholic Church in 1967. Today, Spanish-speaking Christians can choose from dozens of churches to worship in their mother tongue.

There’s a universal message hailing from old Mesoamerica, painted as a mural in the Downtown Canal — “Quetzalcoatl Returns to Look in the Mirror” by Hector Duarte. In it, a feathered serpent deity discovers his own mortality.

Likewise, Juan and Rosaura are discovering that finding a home and building a community might not be enough to live a peaceful, happy life. There is a new sense of fear — with increased focus from the federal government on immigration, hostile encounters also now seem more likely.

This spring, Rosaura, who is 37, was unloading her children from her car outside Target when a man rolled down his window and yelled, “Go back to where you came from!” She was there to buy eggs and milk.

She decided to drop out of an English-language school to protect her family, giving up her progress toward a GED. It’s not her own safety she’s worried about, but her children’s.

“At the end of the day, they have Hispanic traits,” she told Mirror Indy in an interview conducted in Spanish, “even if they’re American, they can get discriminated against.”

She considered selling the house and starting over again in Mexico. But Juan told her, “This is your children’s country.”

‘You can't let go of my hand’

It’s also a country for Dreamers, like Paula.

Paula’s father decided to come to America when he couldn’t afford to buy her shoes for kindergarten.

“That was his breaking point,” the 32-year-old Indianapolis resident told Mirror Indy. “It was little white school shoes, the cheapest you can imagine. But I’ve always been my dad’s world.”

She was a child when she arrived in the U.S., which made her eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. But DACA does not grant permanent residency, and Trump tried to end the program in his first term.

Paula has been married to her husband, who is a U.S. citizen, for nine years. She is eligible for a green card. But with rising fears about green card-holders facing deportation, Paula worries a green card is just the new DACA.

She’s seen U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents ramp up activity under Trump, with more immigrants being deported and green card holders detained. Even U.S. citizens are not immune; a judge found a teenager in Arizona was wrongfully held for 10 days despite his citizenship, while a man born here with parents from Mexico was handcuffed by ICE agents at a Philadelphia car wash.

“The laws and practices are changing so rapidly and causing uncertainty," said Sarah Burrow, an immigration attorney at the Lewis Kappes firm downtown. “Something that may have been true yesterday may not be true today.”

Burrow has watched her clients navigate this new landscape, where the Trump administration has reversed a decade-old policy by allowing ICE agents to search for people at schools, churches and hospitals.

There’s been tension about local law enforcement’s role and if that includes collaborating with ICE.

Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Chief Chris Bailey said in a Jan. 23 statement his department does not have the authority to enforce federal immigration laws. Days later, Gov. Mike Braun hit back with an executive order that said all state law enforcement agencies must “cooperate fully” with ICE.

IMPD said the executive order does not apply to local law enforcement agencies like theirs. “We have not entered into any new agreements with ICE that give our officers federal authority to enforce civil federal immigration laws,” a spokesperson said in an April 28 email to Mirror Indy.

But at the Marion County Jail, which is run by the Marion County Sheriff’s Office, at least 400 immigrants have been detained at some point for ICE, according to jail records obtained by Mirror Indy.

More than a third of them were from Mexico.

Paula is afraid her father will become one of them. He’s been stopped before for driving infractions like failing to come to a complete stop and having a broken tail light. Each is a reminder that the next time could be the last, putting an end to their life together in Indianapolis.

It was 1998 when Paula’s father crossed from Mexico with a dozen other men, guided by a border smuggler known as a coyote. He then worked at a buffet restaurant by day and stocked shelves at Walmart by night, saving up for months so that he could pay a coyote to bring his family safely across the border, too.

Paula remembers putting on her Winnie the Pooh backpack one day and leaving Mexico. She was 6 years old, carrying her family’s birth certificates and documents.

“You can't let go of my hand at all,” Paula remembers her mother telling her. “You have to stay quiet.”

Her uncle lifted her over the border in the state of Sonora in Mexico.

Once the family reunited, Paula and her brother picked up English pretty quickly, helping their parents navigate their new lives.

At the bank, the grocery store and the video rental shop, Paula found herself translating for her mother, and sometimes even having to argue about late fees or overcharges.

“I had to yell at adults at a very young age,” Paula said.

But, she said, becoming a Dreamer under President Barack Obama didn’t bring permanent safety. This has made each moment living under Trump’s presidency sheer terror.

And, for whatever shaky protections she has as a Dreamer, her parents have none at all.

She and her husband have decided not to have children. They want to dedicate their time and resources to Paula’s parents instead. That means giving up monthly brunch dates and downsizing their apartment to save up for an emergency fund.

And they are also considering moving to Mexico, and trying to convince her parents to do the same.

“My parents are scared to go to the gas station because my dad might be stopped,” Paula said. “That’s not why they came here. They came here to give me everything, and it’s my turn to give it back to them.”

‘We are from here, just with a different set of problems’

Hamburgers were the first things Emilio and Maria ate when they crossed the border in 2007.

It was their second attempt after their first was cut short by federal agents. But after that meal, they boarded a flight to Indianapolis.

“Every Hispanic I know is like this: The place they arrive at is the place they fall in love with,” Emilio told Mirror Indy during an interview in Spanish. “I arrived in Indianapolis 20 years ago, and I fell in love.”

Emilio is Juan’s brother, the one who portrayed Pontius Pilate. He’s now 40.

Although they are brothers, their immigration statuses are not the same. That’s because of a special permit, called a U visa, for crime victims who help law enforcement.

Trump hasn’t said whether he plans to eliminate U visas, but the authors of Project 2025 have suggested Trump eliminate or minimize this pathway to citizenship.

One night a few years ago, Emilio told Mirror Indy, he gave a ride to a friend of his sister’s, who was meeting a seller on Facebook Marketplace. Emilio’s children were with them. The meet turned out to be a setup. A group of young men came out with guns and took the cash, as well as the family’s cellphones and watches. Then, the young men started shooting at Emilio’s truck and took his keys.

Emilio, his children and his sister’s friend ran. A woman who was sweeping outside saw them and called the police for them. Emilio told the officers what happened.

Although the event left Emilio shaken, it made him eligible for a U visa, which typically takes about seven years to process. During the Biden administration, though, bona fide determination permits were given to people petitioning for a U visa that were determined to be filed in good faith.

And because she is married to Emilio, Maria also was eligible. So she continued her studies, learning English and obtaining a GED.

In the mornings, Emilio goes to work at a factory. Maria stays home and takes care of their five children. As a family, they like to have board game nights, where they play UNO, Monopoly and the Mexican game Loteria.

Maria, 38, has felt unwelcome in Indianapolis at times, but she feels safer here than in Mexico. Michoacán, where she comes from, is one of the most violent states in Mexico.

“We live in a quiet street. Our children ride their bikes. The neighbors are careful with them. They can play and walk around, calmly and out of danger,” Maria told Mirror Indy in Spanish.

There was a time when certain things reminded Emilio of the night the young men pointed guns at him in front of his children. He said he used to cry and wonder about what could have happened to his family, but then decided to find a therapist. He said that slowly, he was able to regain trust and say hello to strangers again.

The experience with law enforcement also gave Emilio a sense of safety. When he hears about ICE raids or people being deported, he doesn’t believe that will happen to him because neither he nor his wife are criminals.

For Emilio, there’s only one place he calls home, and that place is Indianapolis.

“We’re all different. We each have our own sorrows and pains,” he said. “Don’t see us like foreigners — we are from here, just with a different set of problems.”

Turning the page

At the Statehouse, four high school students sat in the front row. They were there for “The People’s Assembly” put on by the Indiana Latino Democratic Caucus in March of this year.

They listened to a speech from a student their age, a member of the Hispanic honors society at a local high school.

That Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita, a Republican, threatened legal action against Indianapolis Public Schools if they failed to cooperate with federal immigration authorities, made it personal for them.

All four girls are first-generation Americans, born to Mexican immigrants. They have firsthand knowledge of the sacrifices immigrants make and the motivations behind them.

They see it at home every day.

Like Paula, one of the 16-year-old girls translates for her mother. Mirror Indy is not naming her because her parents, who are afraid of being deported, did not give permission. They’re too scared to leave the house these days, so she runs errands for them. That includes grocery shopping for ingredients for her mother’s pozole: pork meat, hominy and chiles fill her family’s cart.

That’s how the girls can make a difference. For Areli, it also means being an outstanding student in her AP classes, where she is one of two Hispanic students.

“That’s one of the ways I take part in leadership,” she said. “People like me aren’t really seen in programs like that.”

For Guadalupe, it’s about giving her grandparents and parents emotional support. She stays informed and tells them they’re going to be fine.

And Marta, Emilio’s daughter and Juan’s niece, feels like the answers are right in front of us. As she hears her classmates in AP History discuss a unit on German immigration to the United States, she wonders why people don’t see the similarities to her own family’s journey here.

“I find that so funny,” the 16-year-old said. “I don’t know how they’re going to judge us for coming to America. They don’t know why we’re coming here. Our parents wanted to give us the American dream.”

She has it within her grasp.

Juan’s Good Friday performance

Two weeks shy of the Via Crucis performance, when the families first arrived at one of the rehearsals, they shook hands. In Mexico, it is a custom to greet everyone with a kiss on the cheek. But these families have called Indianapolis home long enough to blend this gesture of Mexican warmth with Hoosier hospitality.

As they processed around the church, men dressed as Roman guards hit Juan with makeshift whips.

“¡Camina!” they said. “¿O que pretendes que yo cargue la cruz por ti?”

Walk! Or do you pretend I carry this cross for you?

How Mirror Indy reported this story

Since President Donald Trump’s second term began, immigrants of all statuses — citizens, Dreamers, green card holders, U visa holders and those who are living in the U.S. without permission — are seeing their lives upended. Mirror Indy wanted to hear from the people whose stories are often lost in the torrent of news.

Arts and culture editor Jennifer Delgadillo and health reporter Mary Claire Molloy began to narrow their focus on Mexican immigrants, who are the largest immigrant group in Indianapolis. Jennifer and Mary Claire met people at churches, rallies, libraries and workplaces. With every conversation, there was someone new to talk to — another uncle, mother or friend with a different legal status and a story to share.

Delgadillo is Mexican American. She was born and raised in the state of Nuevo León in Mexico, and conducted and translated interviews in Spanish. Some interviews were conducted in English. Audio versions of this story are also being produced in Spanish and English.

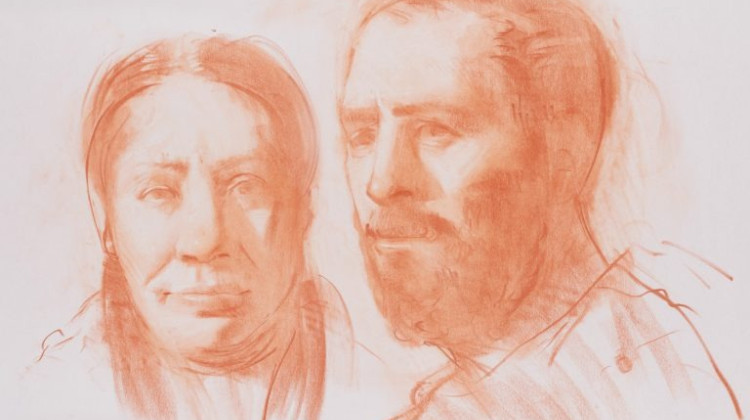

Many people said they feared legal repercussions from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents or harassment if their full names were shared in this article. Mirror Indy agreed to use pseudonyms to protect their privacy. Similarly, Mirror Indy commissioned illustrations inspired by interviews to protect the privacy of the people we spoke with.

Mirror Indy will continue to report on immigration. If you have a story to share, or any questions, comments or news tips, please reach out at the contact information below.

This article first appeared on Mirror Indy and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mirror Indy reporter Mary Claire Molloy covers health. Reach her at 317-721-7648 or email maryclaire.molloy@mirrorindy.org. Follow her on X @mcmolloy7.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.