Indiana lawmakers are considering sweeping changes to local housing and zoning regulations.

Dan Reynolds Photography / Getty ImagesA broad effort to curb local regulations and increase the state’s housing supply — a top priority for Indiana House Republicans — squeaked out of a Senate committee Wednesday after a razor-thin vote and a chorus of warnings from lawmakers in both parties that the bill still falls short and could overreach into local decision-making.

The Senate Judiciary Committee voted 6-5 to send House Bill 1001 to the full Senate, with multiple changes, following two hours of debate. Public testimony and lawmaker discussion both exposed ongoing unease over the bill’s reach, its impacts on local control and whether it would actually make housing more affordable.

All three Democrats on the committee — Sens. Rodney Pol, Lonnie Randolph and Greg Taylor — voted no, joined by Republican Sens. Jim Buck and Sue Glick.

“I do not like taking away local control,” said Glick, of LaGrange. “I think one-size-fits-all does not fit in this case. I want to see the communities have decision-making capacity.”

The deciding vote came from Sen. Aaron Freeman (R-Indianapolis). He pointed to past legislative debates — including over public transit in Marion County — where lawmakers rejected state intervention in the name of local authority.

“The irony of our creator is not lost on me in this moment,” Freeman said, adding that his yes vote was intended to support the bill’s sponsor and allow time for fixes. “That’s the only reason I’m voting yes.”

Other senators who voted to advance the bill aired reservations, too.

“This bill has some problems, and if this were the final vote today, I’d be a no,” said Sen. Eric Koch (R-Bedford), who voted yes, for now.

“I don’t like that it is stepping on local control,” said Sen. Scott Alexander (R-Muncie), another yes vote. “There is a lot of work left to do,” he continued, noting he reserved the right to oppose the bill on the floor “if we don’t very quickly find a better place for this.”

Committee chair Sen. Cyndi Carrasco (R-Indianapolis), also supported the bill while criticizing its approach.

“I do have deep concerns about taking a one-size all-approach across the different, varied communities that we’ve heard from here,” she said. “I think there’s more work that could be done on this to be able to get to a point where we’re taking a step in the right direction.”

Emphasis on opt-outs

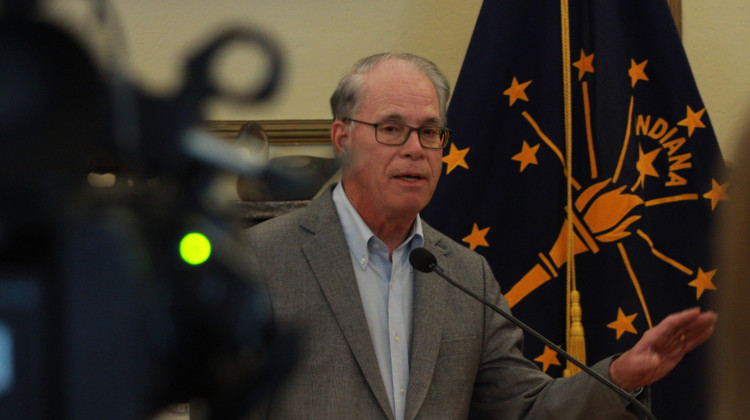

House Bill 1001, authored by Rep. Doug Miller (R-Elkhart), is designed to address Indiana’s housing shortage by limiting local zoning rules, streamlining approvals and expanding what types of residential development must be allowed without public hearings unless a city or county formally opts out.

The bill previously passed the House 76-15.

Miller has repeatedly argued that “unnecessary regulations” are driving up housing costs and suppressing new construction and studies show a growing affordability gap across the state.

“Indiana needs about 50,000 homes today,” Miller told senators on Wednesday. “We had to put a stake in the ground and say, ‘We need to do this now.’”

At a high level, the bill restricts local governments from regulating certain residential design elements — such as exterior features — unless they adopt an ordinance opting out.

It also establishes categories of “permitted uses,” meaning some housing projects could move forward without zoning hearings if they meet existing local standards for setbacks, lot size and other requirements.

The committee adopted two amendments that significantly reshaped the bill, however.

One change modifies long-standing limits on housing authority projects by raising allowable average construction costs per room and loosening financing rules. It increases the cap from $2,000 to $4,000 per room for certain projects, and from $10,000 to $15,000 per room for housing designed for people with low incomes. It also allows projects to exceed those limits by “an amount necessary to make the project financially feasible,” rather than a fixed $750 per room.

The second amendment significantly rewrote multiple provisions, narrowing where the bill’s permitted uses apply and expanding opt-out provisions.

Under the amendment, many of the bill’s automatic allowances would apply only to property located near public transit routes, within riverfront development projects, or in redevelopment areas already zoned residential or commercial.

It allows at least two single-family homes or one duplex on residentially zoned lots, and mixed-use or multifamily housing on commercially zoned property. Accessory dwelling units and commercial-to-residential conversions would become permitted uses only if a local government does not opt out by Dec. 31.

The committee also nixed language that would have made housing developments by religious institutions a permitted use, instead urging lawmakers to study that issue during an interim.

Other provisions require annual housing progress reports to the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority starting in 2027; mandate updates to the state’s storm water manual; cap flood-plain mitigation ratios at three-to-one in certain cases; refund regulatory fees when permit deadlines are missed; prohibit some electrical and emergency system requirements after mid-2026; and extend the life of residential tax increment financing districts to 25 years.

Miller described the amendment as the product of months of negotiations with local officials and stakeholders.

“It basically makes it so that all of the provisions that are currently in the legislation that were not originally opt-out pieces are now opt-out,” Miller said.

He also emphasized that “permitted uses” do not override local building standards.

“The local regulations for setbacks and side yards and everything that would go with building a project remain in place,” Miller said. “You have to meet all those, or you can’t do it. It’s just that simple.”

Local officials push back

Despite the changes, more than a dozen local officials and planning experts who testified Wednesday were still opposed.

Suzie Weirick, an Elkhart County commissioner and president of the Indiana County Commissioners, warned that key sections still amount to state preemption and said communities need assurances that any cost savings reach homebuyers.

“We support residential development and growth of all types of housing, including affordable housing,” Weirick said, “but not at the expense of the health and safety of our residents and taxpayers.”

Johnson County Commissioner Brian Baird said the bill “significantly limits local planning and zoning authority” while failing to require affordability outcomes.

“A one-size-fits-all zoning mandate from the state does not reflect the realities of rural, suburban and urban counties across Indiana,” he said.

Others echoed concerns about infrastructure, septic systems, storm water, traffic and emergency response — especially in rural areas.

Michael Jabo, with Porter County’s Development and Storm Water Department, warned that higher-density development without infrastructure distinctions could “risk pollution, traffic congestion, and slower emergency response in rural areas.”

Deborah Luzier, with the Indiana Chapter of the American Planning Association, said the bill conflicts with Indiana’s home-rule framework.

“These provisions are in drastic conflict with, and bypass, the procedures for establishing comprehensive plans,” she said.

‘We’ve got to do more’

Supporters, meanwhile, argued that state action is necessary to address Indiana’s housing shortage and rein in regulatory costs.

“This is a critical issue facing not only Indiana, but the country,” said Rick Wajda, head of the Indiana Builders Association.

He said some Indiana communities are “doing it right,” but others are instead adopting local rules that increase the price of new construction.

“Those regulations now account for about 24% of the cost of a new home,” he said, citing a median new-home price of $484,000. “Only about 17% of Hoosier households can afford that. The average first-time homebuyer today is 40 years old. We’ve got to do more.”

An official with the Indiana Association of Realtors said the state’s housing crunch is fundamentally a supply problem, with household growth outpacing construction in recent years. Indiana has added roughly 125,000 owner-occupied households over the past five years, but built only about 100,000 new housing units during that time, according to the group.

“Inventory, inventory, inventory continues to be the concern for us,” said Maggie McShane, the association’s vice president of public policy. “At every level of government — the national level, the state level, the local level — the concern and desire and need for more housing exists.”

“There are four main components that add to the cost of housing and make it harder and harder for the next generation to get into ownership: the cost of land, the cost of labor, the cost of lumber — and laws,” she continued. “Laws are something we all can do something about.”

Terre Haute Mayor Brandon Sakbun urged lawmakers to focus on ”actual”drivers of housing costs.

“Affordability is not a buzzword,” he said. “I caution this group to show municipalities why zoning and building fees are creating the issues instead of the cost of updating or adding new infrastructure — because that’s the number one concern builders bring to me.”

Habitat for Humanity of Indiana State Director Gina Leckron emphasized that local mandates can translate directly into higher monthly costs for low-income homeowners, sometimes putting otherwise affordable homes out of reach.

In one community, she said, a local ordinance required the nonprofit to build a two-car garage, adding about $25,000 to the cost of the home. That increase translated into roughly $70 more per month on the mortgage, which the buyer could not afford. She said Habitat stepped in and subsidized the difference.

“These are the kinds of things that are happening, that we need your help with,” Leckron said. “So many construction costs are out of our control, but laws are not.”

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: info@indianacapitalchronicle.com.

DONATE

DONATE

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.

Support WFYI. We can't do it without you.